How can transmission during pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding be prevented?

People living with HIV can give birth to HIV-negative babies.

There are recommended precautions for those living with HIV to give birth to HIV negative children:

- Being on effective HIV treatment during pregnancy.

- Making a careful choice between caesarean section and vaginal delivery.

- Not breastfeeding.

- Giving the new baby an anti-HIV drug (infant PEP) for a few weeks.

By doing these things, the chances of the baby having HIV become very low – under 1%. If you're on HIV treatment and have an undetectable viral load, the chances are lower still: 0.1%.

Here's how transmission can occur

- During pregnancy – the foetus acquires HIV through blood crossing the placenta.

- During delivery – the baby acquires HIV through cervical secretions or blood during childbirth.

- During breastfeeding – the baby acquires HIV through breast milk or blood during breastfeeding.

These factors increase the risk of passing HIV on to the baby:

- Being ill because of HIV, especially if you have tuberculosis (TB).

- Having a high HIV viral load and a low CD4 cell count.

- Your waters breaking four hours before delivery, or earlier.

- Having an untreated sexually transmitted infection (STI) during pregnancy or at the time of delivery.

- Using recreational drugs, particularly injected drugs, during pregnancy.

- Having a vaginal delivery (rather than a caesarean delivery) if your HIV viral load is detectable.

- Breastfeeding.

How does HIV treatment prevent transmission of HIV during pregnancy and birth?

Everyone with HIV is now recommended to start treatment at diagnosis whatever their CD4 count.

There are two different ways in which anti-HIV drugs act to prevent transmission:

- They reduce your viral load so your baby is exposed to less HIV while in the womb and during birth. The aim of HIV treatment is to get, and keep, your viral load to undetectable levels. (If your viral load is below 50, it’s called undetectable although most clinics in the UK can measure below 20 copies/ml.)

- Some anti-HIV drugs cross the placenta and enter your baby’s body, preventing the virus from ever taking hold. Newborn babies are given a short course of anti-HIV drugs after they’re born.

You can reduce the risk of HIV transmission further by having a managed delivery. Your doctor will look at your viral load when you are 36 weeks pregnant and discuss options with you.

Antenatal care if you are living with HIV

You're likely to be looked after by a team of healthcare workers during your pregnancy.

You’ll still get your care at your HIV clinic. But, as well as your HIV doctor and clinic staff, you’re likely to see an obstetrician (a doctor who delivers babies), a specialist midwife and a paediatrician.

Other people you may see, depending on the kind of help you’ll need, could include:

- a peer support worker

- a community midwife

- a counsellor

- a psychologist

- a social worker or a patient advocate.

They’ll help you with issues like problems with housing, finances or alcohol and drug use. They can provide support and advice on your eligibility for free NHS treatment and other financial help, such as help with formula feeding.

Like all health professionals, the members of your antenatal care team are bound by confidentiality guidelines and will not disclose your status to anyone without your consent.

How should I feed my baby?

The safest way for you to feed your baby is to bottle feed using formula milk. There is zero risk of HIV being passed on after birth this way.

You may have mixed feelings about bottle-feeding (especially if other people you know breastfeed), but remember that over 8 out of 10 people in the UK are feeding their babies with formula milk by the time the baby is 3 months old.

Holding your baby in a breastfeeding position with lots of eye contact and skin-to-skin contact will create the same close bond.

If you are not breastfeeding, people will not think it is unusual, or think it has anything to do with being HIV positive.

Family and friends may ask why you aren’t breastfeeding, and dealing with their questions can be difficult. If you don’t want to talk about HIV, you could say that you are not producing enough milk, that you have mastitis (inflammation of the breast), or that you have cracked nipples.

If you choose to breastfeed:

If you are on treatment with an undetectable viral load and choose to breastfeed your baby, then see your doctor before you start. Your clinic team can help you make it as safe as possible for your baby, but it will not be as safe as using formula.

You should breastfeed your baby for as short a time as possible, and the baby should only have breastmilk for the first 6 months, and not formula or cow’s milk too.

Stop breastfeeding and start using formula milk if:

- your HIV is detectable

- you or your baby have tummy problems

- your breasts and/or nipples show signs of infection (cracked, sore or bleeding nipples).

Will my baby need HIV treatment and testing?

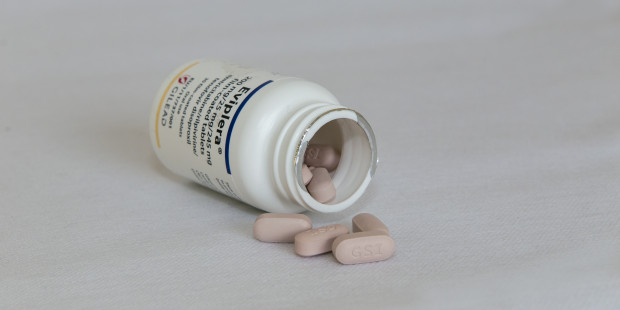

Yes, your baby will need to take a special liquid form of anti-HIV drugs for four weeks after birth. This doesn’t mean that the baby has HIV.

To check that your baby has not acquired HIV, HIV tests will be done several times:

- just after birth

- at six weeks

- at 12 weeks

- and a final HIV antibody test at 18 months.

If these tests are negative and you've never breastfed, you'll know for sure that the baby does not have HIV.